My earliest memory of growing up in Tokyo is in kindergarten hiding behind the trunk of a giant tree.

“She has to be somewhere,” someone whispered. “I bet she’s hiding again,” another snickered.

Like a rabbit sensing danger, I waited until their voices faded, then dashed past a group of giggling children to my usual hiding spot—the bathroom.

No one looked for me there, not even the teachers—it was perfect. I ate lunch in that bathroom. I cried in that bathroom. I hoped in that bathroom—desperately aching for a warm body to wrap their arms around me.

My dad was a diligent man who grew up in Nepal with a big family of five brothers and three sisters. He liked to recite over and over again with an animated face how he walked to school barefoot because his family couldn’t afford new shoes.

Despite that, he won a scholarship to a graduate program at an Ivy League in New York, and landed a job as a civil engineer in Tokyo.

He was brown—Indian brown. My mom was fair—Bollywood fair. When we walked together as a family, I instinctively clung to her. I knew, even as a child, that Dad’s skin was “wrong,” and Mom’s was “right.”

I was a mix of both—‘‘olive,’’ like it says on my Nepali passport.

I thought things would get better after kindergarten. I was enrolled in an international school full of gaijins (foreigners). I learned that the streets of Tokyo were where the real danger lurked.

Every day, my younger sister and I walked past a large Japanese public school full of eager children playing during recess. One afternoon, we were eating ice cream on the way home from school when I noticed three boys stomping toward us, their faces scrunched in disgust.

One of them—a chubby boy— leaned inches from my sister’s face and growled, “Stop eating Japanese ice cream!” Then he slapped the cone out of her hand.

Splat.

I dropped my own ice cream, grabbed her hand, and we ran, leaving a remnant of a battlefield. After that, we didn’t dare take the same route again.

Hiding became a recurring theme of my childhood. I learned early that I was not the “right kind.” Not my nose, not my skin, not my eyes. Silence was the only way to survive, and I was a walking warning label. It was like my very presence disturbed the order of things, like I was a disruption just for existing.

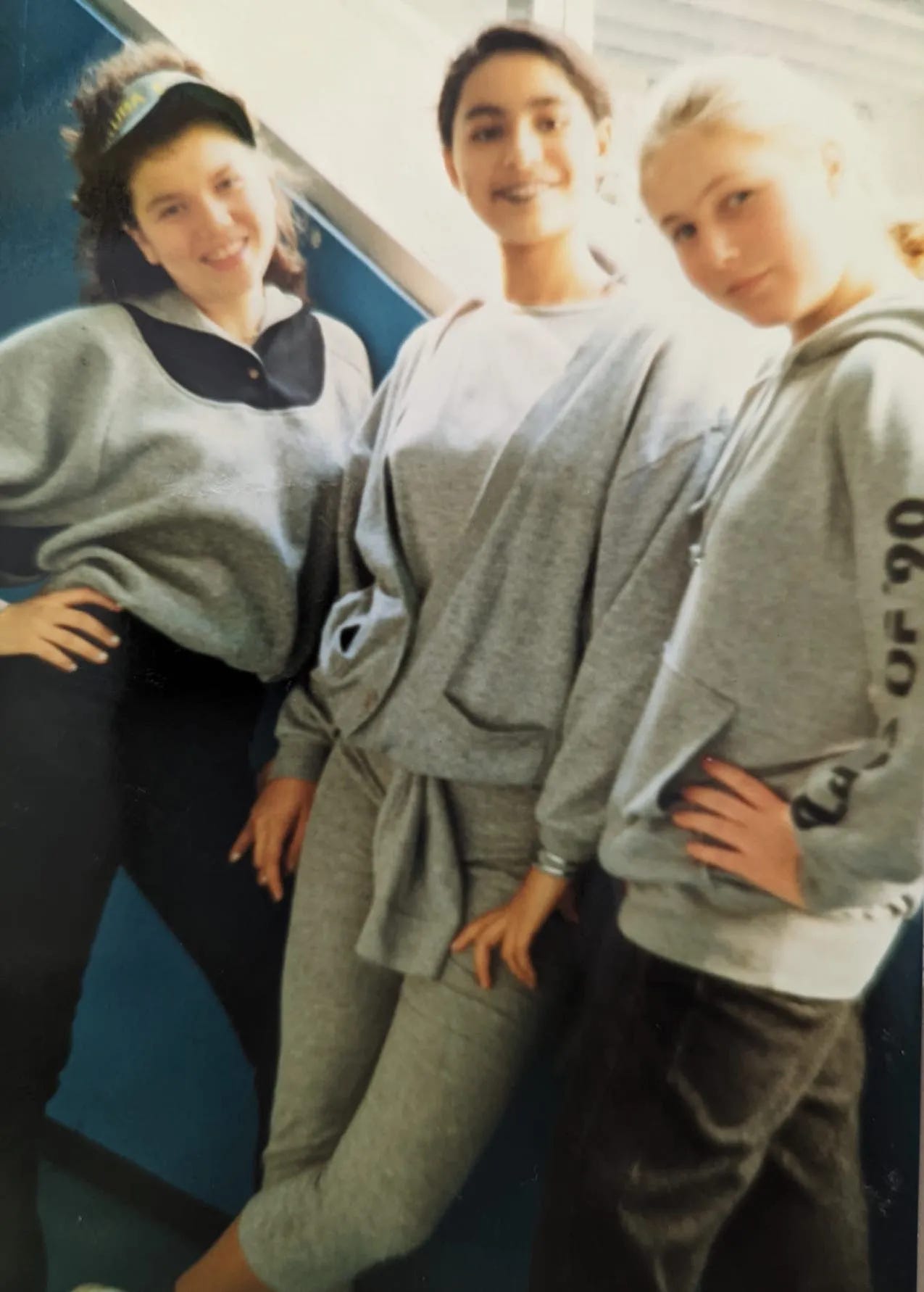

My international school was more tolerant. My bestfriend was a feisty Yugoslavian girl named Jackie. She wore red lipstick to school and was constancly reprimanded for it, but she carried herself like a boss, that like-me-for-me-or-fuck-off-kinda air that pulled me to her.

It was nice to have a best friend, especially one who was white and pretty. I walked beside her on the streets of Tokyo like a bodyguard, except she was protecting me from the prying eyes of the Japanese. As long as I glued myself to her, I was safe.

I loved Japan. I considered it my motherland. We visited Nepal every two years, but I sounded like a foreigner speaking Nepali, which I didn’t know until my cousins started imitating me. My connection to my supposed home country felt like a portrait of Mount Everest hanging on a wall, a reminder that it’s there but I’ll never conquer it.

My mother spoke Japanese like a native, like I did. When her friends visited, they would say: “Nihongo jyouzu ne!” (You speak such good Japanese!)

Of course I do, I wanted to say, I grew up here. Then would come the questions:

“Do you miss Nepal?”

“You must miss your family.”

“What a beautiful country it must be!”

I would nod, but all along, I would be thinking: Didn’t they understand? Japan was my country too. I moved here when I was two. I bowed at all the right moments and understood the subtle social ranks of the language. But I was still just a visitor and would never be one of them.

Perhaps I had too high of an expectation. At my international school, my white friends were my human shields. The Japanese gawked at my them like starstruck fans.

But the ones who had it best were the hafus—half Japanese, half something else. Some were scouted on the streets by talent agencies looking for models. Their faces decorated billboards, commercials, and magazines. They were the right gaijin.

I learned to wear sunglasses even on cloudy days—anything to hide, anything to blend in. At night, I would stretch my eyes to the sides in front of the mirror, trying to make them look more Japanese. I hated my nose—it stuck out like a nail.

It’s not that I wanted to be invisible, but being seen felt dangerous, like the Japanese proverb: The nail that sticks out gets hammered down.

When Dad retired, my parents moved back to Nepal. They were always guests in Japan. It was time to go home.

But me?

I’ve renewed my passport many times since leaving, which means there’s no official record that I ever lived in Japan. 17 years of struggling to fit in erased and exiled.

After I left Japan, I carried its trauma with me. For years, I didn’t talk about my childhood, not because I had forgotten about it, but because I didn’t yet have the words. I moved countries and made new homes, but an undercurrent of emptiness followed me. I kept searching for a place that would let me feel whole.

Now, decades later, I live in Germany with my husband and our six-year-old son. He’s half German, fluent in three languages— Japanese, German, and English—and living in a country that accepts him as he is, which is intentional.

I never ever want him to live in a place that isolates, bullies, and crushes him. I’m raising him with the tenderness I craved as a child, fiercely protective of his right to belong, to take up space without waiting for permission to exist.

As for me, I’m starting over. I’ve come full circle to a place that reminds me of my upbringing. I’m learning a new language and culture, and figuring out where I belong in this strange country I now call home.

I don’t speak the language well enough. I have no mom friends or any friends for that matter. All around me, everyone’s white, and I’m the only brown person in the neighborhood. My childhood scars are still very much still there. At times, I get so anxious that I can’t step out of the house. It’s like the body remembers everything, every little thing.

The difference is, I’m no longer that helpless child, although that child lives in me. Childhood wounds hurt, but they don’t define me.

I’m a happy mom with a happy child and a good, giving man. Having lived in Tokyo, Hawaii, San Francisco, Nepal, Thailand, and Myanmar, I know belonging is not a passport (I became American at 25) or a place.

And as much as I adore my husband and our boy, they can be taken away from me. When I was 37, my mom died, my home perishing with her. I learned that belonging is not a person.

So, what is belonging?

I think belonging is not a full stop. It’s not something to cultivate outside yourself, but rather an inner knowing. I haven’t figured out yet how to soften that intense fire in me that struggles to have a voice.

The roots are so far down, and the answers will bloom after many springs, and I must be patient.

Oh June this is beautiful! So powerful. So poignant. So relateable to me on one level and yet I carry the privilege of white skin. I look forward to reading more from you here. So lovely to read your words again my lovely xx

This is so heartbreaking and beautiful and just I have no words.

You may have no friends in Germany but you have one cheering you on always from Canada